September 2025

Note: There is very little information about how to be a pregnant athlete. Everyone has a different experience with pregnancy. By sharing this information my intention is to be transparent about my experience in the hope that it helps other pregnant athletes. Also note that this post has a negative tone because I wrote most of it while pregnant. I kept the tone negative because that was authentic to my experience of pregnancy.

I’ll share a post soon summarizing my experience with pregnancy & sports overall.

Background

One of the races I was registered for in 2025 was Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc (UTMB) 100 mile. I won an entry into UTMB at Kodiak in 2024, and UTMB would have been my second 100 miler. However, life had other plans for me and by the time UTMB rolled around I was 6 months pregnant and mostly unable to run. I deferred my entry in June when I entered my second trimester but we decided it would still be fun to go to Europe for two weeks around the time of UTMB and try to fastpack parts of the Trail du Mont Blanc (TBM), the 175-ish km course around Mont Blanc that makes up the majority of the UTMB course.

For context, I had a low risk pregnancy but suffered from nausea from week 5 to week 38. This is within the range of normal but pretty unlucky. I also had fatigue, food sensitivities and aversions (including strong aversions to cookies and butter 😥 ), and pelvic pain in my first trimester. I had a few nausea free days in my second trimester but it came back almost full force in my third, along with congestion, heartburn, insomnia, restless leg syndrome, and more pelvic pain. Pregnancy is certainly the least enjoyable endurance event I’ve ever participated in, and unfortunately also the longest. Mercifully, one of the only things that helped me feel better was exercise, including hiking, skiing, running, gravel and mountain biking, yoga, and the gym.

When I planned this trip in June 2025, I had us doing the entire TMB over 7 days and I envisioned us running the route (slowly). However, by the time September rolled around I was TIRED. We had a few fun outings in Chamonix (Aiguilles Crouches, Via Alpina, La Jonction) but I had to take multiple rest days after each, which is unusual for me. Also, running became pretty uncomfortable for a few weeks starting the week we got to Chamonix (I was getting round ligament pain which is an uncomfortable sharp pain in the belly that only goes away when you stop running. Pregnant people will be familiar with this cursed feeling). As a result I was mostly hiking instead of running, which made everything slower than I’m used to, and I felt that 20-30km days on the TMB might be both too hard and too slow for me. I should also mention that I am NOT a hiker. The last time I did a multi-day hiking trip was in 2009 when I hiked the West Coast Trail. All of this meant that we needed to shorten our TMB route a little. Audree and Jeff gave us some advice about which portions of the TMB would be best to skip and which shouldn’t be missed, so we did a bit of tentative contingency planning before leaving which came in handy later.

Day 1: Into the Mist

Bus from Chamonix to Le Tour, Le Tour to Col de Balme hut

The first day was about 8km through mist, fog, and clouds from Le Tour to Col de Balme. We got a few glimpses of the mountains around and the views would have been stunning in better weather. Not too much to say about this day except that the trails looked exceptionally runnable and I attempted a few minutes of lumbering whale-jog before calling it and accepting my fate as a pregnant hiker.

Col de Balme is a beautiful refuge just barely on the Swiss side of the France-Swiss border with 30 or so beds in dormitories. The hut was fully booked and the staff turned down requests from several campers to stay indoors when the weather started to get bad in the evening (incidentally our dorm room had 4 extra beds, so the hut custodian may have just been trying to keep the loud and fairly drunk campers out of the hut). We had a dinner of chilli and went to bed pretty early. Sleeping on a 1000 year old bunk bed in a too-tight sleeping bag liner at 2000m while pregnant was hard, and I only got a few hours of sleep, but despite this, I thoroughly enjoyed my first refuge experience in the Alps.

Day 2: Oh fuck, chilli again?

Col de Balme to Champex-Lac via Fenetre d’Arpette

The next morning weather was better and we decided to take the Fenetre d’Arpette route through the mountains instead of the regular TMB, on the recommendation of the hut custodian. It was a bit shorter in distance but more technical and with better views of nearby glaciers. To get there, we descended into a valley (where we had an excellent slice of peach pie) and then out the other side, beside a big glacier. Weather was a bit mixed with some rain and snow near the pass, but overall pretty good. We arrived at our next refuge, Relais d’Arpette, midafternoon and enjoyed cold beverages and board games (we brought Quoridors, a fun and portable board game made locally in Squamish, gifted to us by our friends Myrika and Vincent) until dinner. We were surprised to once again be served chilli for dinner, and I secretly started to grow weary of the food in Switzerland (though they partially redeemed themselves by also serving picked beets in the salad, anything pickled being the key to my heart while pregnant). Relais d’Arpette was one of the few huts that still had availability when I booked in June, and a private room with a ‘private’ (but shared with the other rooms nearby?) balcony was over $400CAD per night. The private rooms had great showers and comfortable beds. Once again, my poor pregnant body resisted all attempts at sleep.

After only two days on the trail, I was already totally cooked and decided we needed to activate one of our contingency plans. We decided to cut out most of the section between Champex-Lac and La Fouly and head for Courmayeur, since we knew it was mostly valley walking. I was pretty over the Swiss cuisine (chilli??) we’d experienced so far, as well as the exchange rate.

Day 3: Crying in Switzerland

Champex-Lac to Issert, bus from Issert to Ferret, Ferret to Lavachey, bus from Lavachey to Courmayeur

On day 3, we left Relais d’Arpette early and walked down the TMB towards Champex-Lac and then a small town called Issert. We briefly crossed the Swiss Peaks 360 course and encountered a few utterly wrecked runners. We had to wait for about an hour for the bus so we paid $50 for some bad coffee and sandwiches and then walked through town to the bus stop on the far end of town. (The Swiss bus system caused us a bit of stress because we weren’t able to buy tickets online or in store, and couldn’t find much information about them. In the end, we were able to pay for our tickets on the bus with credit card.) I cried from fatigue and frustration as we walked, generally sick of being pregnant, done with eating chilli for dinner, and tired from not sleeping well from a combination of restless legs, heartburn, and being the size of a small whale. Though it was a perfectly sunny day, rain fell on us from the cloudless sky while we walked to the bus stop.

The bus took us a few stops past La Fouly to Ferret, and we began to hike uphill through cow pastures towards Grand Col Ferret, where we got our first view of the Italian side of the Mont Blanc (or Monte Bianco, at that point) massif. As soon as we got to Italy the people were friendlier, the food tastier, and the views better. This was one of my favourite sections of trail and I soon forgot my dramatics from the morning. I can’t wait to run here in the future, the trails are smooth and flowy and the views are some of the best I’ve ever seen. We stopped at a refuge or two for snacks and espresso and eventually made our way down to Lavachey where we caught a free tourist bus to Courmayeur. I couldn’t recommend this section enough and will definitely return here.

Day 4: The best breakfast buffet of my life

Because we’d cut out a huge section of the TMB in Switzerland, we were able to take a rest day in Courmayeur. Similar to Chamonix, Courmayeur is stunningly beautiful. I was immediately happy we had changed our plans and looked forward to two nights in the same bed and not chilli for dinner. We went to a nearby restaurant for dinner and (unsurprisingly) stumbled upon really good pizza. On the recommendation of our friends Mercedes and Nico, we stayed in Le Massif, a hotel near downtown in Courmayeur. The bed was super comfortable and the breakfast buffet was like nothing I’ve ever seen. If you’re in Courmayeur, go here! Our first morning in Courmayeur we spent over 90 minutes at the breakfast buffet enjoying good coffee, made to order omelettes, baked goods, and nearly every other breakfast item we could think of. I spent the rest of the day relaxing in the hotel room (pictured), with a goal to move as little as possible and sleep as much as possible (pictured), only leaving three times (all to get food), while Eric went on a 30k training run in the mountains South of town (partially following the TMB).

Day 5: Welcomed back to France by the perfect crepe

Bus from Courmayeur to Val Veny, Val Veny to Le Chapieux

The next morning we once again enjoyed the buffet breakfast (just one hour this time) and then took a bus to Val Veny to cut a few km off an otherwise pretty long (30km) day. From there we began to climb and then descend towards the border with France, enjoying incredible views and great snacks at the refuges. This is an interesting section of trail with a lot of history from World War 2. There are tunnels in the mountains and visible foxholes. As we descended into France, we stopped at a refuge that served DELICIOUS ham, egg, and cheese crepes. That afternoon we arrived in the tiny village of Le Chapieux and checked into our hut, Refuge de la Nova. The hosts were friendly, the food was delicious, and the room was comfortable.

Day 6: “Oh wow she’s pregnant”

Le Chapieux to Les Contamines

The next day, our second to last, we climbed up to Col du Bonhomme and then down to Les Contamines. One of our favourite stops was at Chalet Refuge de Nant Barrant where we had great food in a lovely garden setting. This day had some more great views and was very busy, with nearly everyone going in the opposite direction as us (we did the route clockwise instead of counterclockwise because there wasn’t much hut availability when I booked in June). We realized most people would have been just a day or two into their TMB at this point, and people were definitely struggling on the climb. I had a lot of people look at me with wide eyes, asking if I was doing the whole TMB while pregnant. We wondered if they’d be able to close the loop. We arrived in Les Contamines midafternoon and checked into our accommodation, Le Pontet. A campsite/cabins/dorm situation with the vibe of an American KOA, which is to say I would not recommend it, but it was fine. Once again, no sleep for me.

Day 7: The faster I hike, the sooner I get to Chez Richard

Les Contamines to Bellevue Gondola, Bellevue Gondola to Les Houches, bus from Les Houches to Chamonix

Our final day was from Les Contamines to the top of the Bellevue gondola above Les Houches and we did a variation over Col du Tricot. This was a relatively short day, 13km with 1300m of elevation gain. We stopped for food at two refuges, met a wonderful, floofy, and very dreadlocked dog, and made it to Bellevue gondola early in the afternoon. The bus from Les Houches to Chamonix stops at the gondola, so it was an easy trip. We headed straight for Couloir coffee for sandwiches and then Chez Richard for their heavenly croissants. We then headed up to our hotel, Auberge du Bois Prin, cleaned up, and went out for dinner (would highly recommend this hotel, we stayed here a few times during our trip. Auberge du Bois Prin and Le Massif were the only two places I could sleep while pregnant).

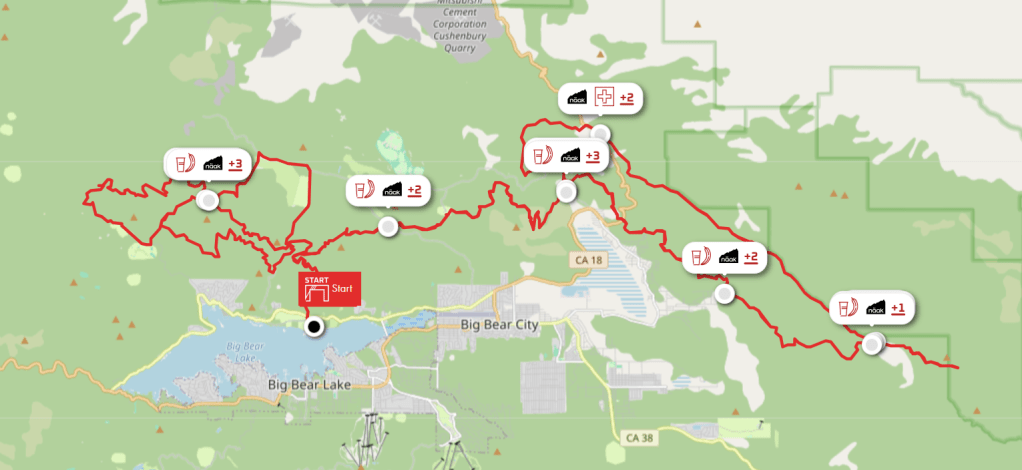

(Note the Strava screenshot showing that I pretty much never hike)

TMB while pregnant: Takeaways

Overall this was a great trip, even if I was so tired I cried every few days. There were a lot of great moments during the hike and I really enjoyed the views and the food. I often think about how cool it is that I took my baby around Mont Blanc on foot while I was pregnant.

What I’d do again:

- Use poles. They were essential.

- The TMB route. It was a good option for me while pregnant for a few reasons:

- So much food. I needed to eat frequently throughout the day, which was easy with so many refuges around.

- Non technical trails. As I became more pregnant, my balance got worse. The TMB trails are not technical at all, so I was able to hike without any worries about losing my balance, tripping, or falling. The downside to this was that it was a little boring at times and I wished I was moving faster. I can see why this is a great trail to run.

- Flexibility. This route has a ton of flexibility. You can skip sections and take a bus, you can stay in a hotel instead of a refuge, you can take an alternate route, you can take an impromptu rest day. We used a lot of these options and were super grateful for it.

- Lots of amenities. We hardly had to carry anything (see gear list below) which was great for me because I was already carrying around about 15lbs of baby plus her accessories at that point

What I’d do differently:

- Planned for more rest days, and/or planned a different approach where we stayed in one place and explored around, and/or adjusted our route and booked more hotels. I didn’t realize how uncomfortable and tired I would be at this point in pregnancy. Comfortable hotel beds were the only place I had a chance of sleeping. I found that while pregnant I could typically do 1-2 hours of exercise a day for a few days back to back, or one long day of activity, but not 4-8 hour days back to back.

- Not stay in any dorms.

If you’re pregnant and planning to hike the TMB, please reach out! I’d be more than happy to share more information or chat about it.

Gear List

- Pack: Arcteryx Norvan 14L pack

- Poles: Black Diamond

- Shoes: Norda 001

- Daytime Clothing: Rabbit T shirt in size large, Crz Yoga maternity shorts, Arcteryx Taema sun hoody, Janji sports bra, Arcteryx aerios cap

- Pregnancy belly band: Maternity FITsplint

- Nighttime Clothing: Arcteryx merino T shirt and long sleeve T shirt, Lululemon Align leggings

- Western Mountaineering sleeping bag liner (would NOT recommend using while pregnant, it’s too narrow)

- Eye mask, ear plugs, and little comforts go a long way on this route