Trip: May 2024

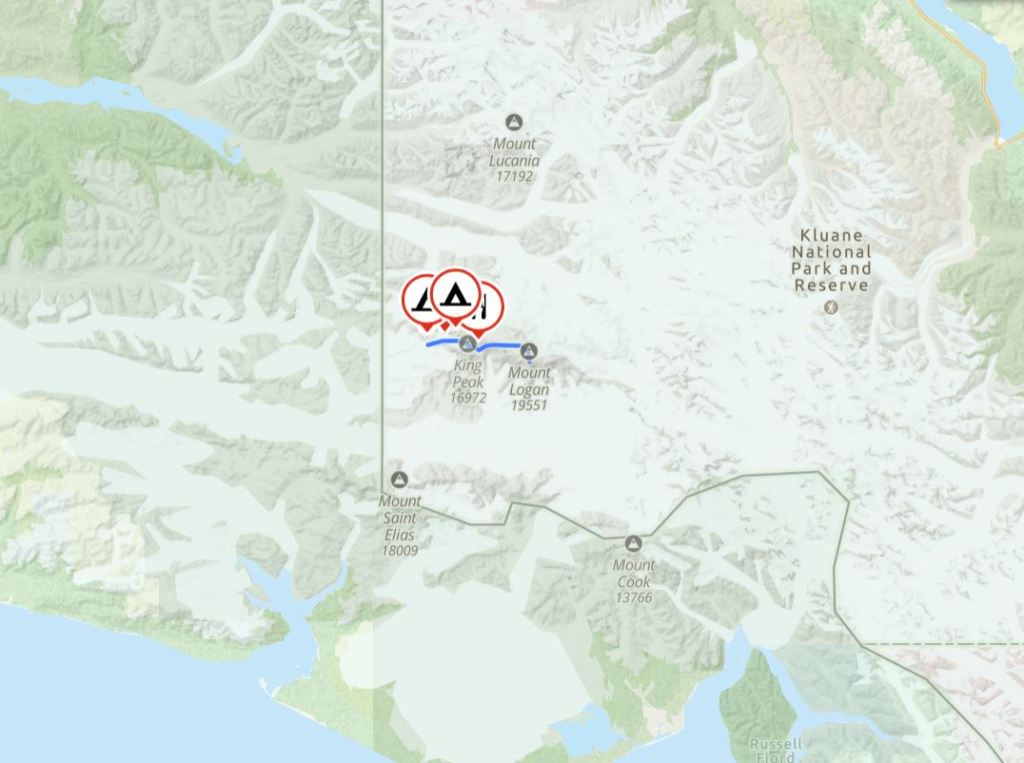

The plan was to fly from Silver City, the small airport 45 minutes from Haines Junction, to the Kings Trench on Friday, May 10, 2024.

A bad stretch of weather starting on May 1 meant Icefield Discovery, the one-plane operation serving Mt Logan and the surrounding area, was unable to fly for the first two weeks of May. We were in touch with Sian, the owner of Icefield Discovery, and changed our plans slightly in response to the weather, leaving Squamish a few days later and arriving in the Yukon on the weekend of May 11.

We spent a few days repacking and tying up loose ends in Haines Junction, and made our way to Silver City on Monday, May 13. Somewhere between Squamish and Silver City, a mouse made its way into our truck and was eating our snacks. We had to fully unload the truck twice before we found it, and it looked like it had been thoroughly enjoying our food.

After being grounded for 13 days, Sian and her team were optimistic that they’d start to work their way through the backlog of skiers and mountaineers waiting to get into the mountains. A few groups ahead of us had waited for a week or longer to fly and had finally given up, so we were lucky and were the second group in the queue.

On Tuesday, May 14, we made it to basecamp on Mt Logan’s King’s Trench route. Our flight in took us over the first part of our route and we took advantage by taking photos from above so that we could better navigate through the crevasses on our way to Camp 1. Basecamp is at approximately 2800m and is just a few kilometers east of the Alaska border.

Basecamp: Day 1

We arrived around 1:30pm and immediately began to set up basecamp. We dug a platform for the tent and built a small wall to shelter the tent from the wind, which was coming from the west. Some clouds began to gather around the pass where we had flown in, and we heard a plane approach and then turn around as we set up camp. We later learned that our future friends from Montana were in that plane, which had to turn around just minutes from landing at camp because of the wall of clouds. This would become a trend.

Around 5 or 6pm, we carried a load of food and fuel up to Camp 1. As we worked our way up, fog rolled in and it began to lightly snow. The crevasses were enormous so navigation was relatively easy. We buried our cache around 3100m and skied back to basecamp with our sleds flapping behind us. It was now about 9:30pm and we began to make dinner. The original plan was quesadillas with chicken, peppers, and beans, but we quickly decided that just cheese would do. Best quesadilla I’ve ever had.

Camp 1: Days 2-4

The next morning the sun was out and it was a beautiful day. We woke up at 7 and sent an InReach message to Sian with a weather report so that she could plan her flights for the day. There were several more groups booked to come to basecamp over the coming days. She reported back that unfortunately the plane had a mechanical issue and was unable to fly for a few days, so we’d get Logan all to ourselves for a few more days. We later heard that a fireball had shot out the back of the plane as the Montanans tried to fly in after us on May 14.

We packed up camp and were ready to start moving around noon, which was not ideal but necessary because of our late night. About 6-10cm of snow had fallen overnight and we moved at a crawl, breaking trail and pulling our heavy sleds. We ate and drank occasionally, and around the time we passed our cache, we were both feeling tired and hungry. We arrived at Camp 1 in the late afternoon, had a big snack (which greatly improved our wellbeing), skied back to pick up our cache, and then set up camp.

Camp 1 is around 3300m and sits on a large patch of glacier, about 2km wide, between two 4000m ridges. The north-facing ridge to the south is heavily serraced, and the south-facing ridge to the north is exposed granite with small gravelly rock at the bottom. We decided we wanted to be farther away from the serracs, so we set our camp 1 closer to the north end of the glacier.

Throughout the afternoon we heard small rocks falling and sliding down the granite ridge, which felt quite close. When we looked at our map, we found that we were several hundred meters away from the ridge and safe unless there was a massive and unlikely rockfall. We had to balance our proximity to the rocks with our desire to be very far away from the serracs on the south side of the trench, but it still felt uncomfortable. The scale on Mt Logan is difficult to comprehend. Everything there is huge, distances are foreshortened, and the endless snow and ice made us lose all perspective.

Reflecting on the day, we realized we needed to eat more frequently to keep our energy levels up and prevent bonking. Even though we were still relatively low, the altitude was affecting us a little by making us need more energy but feel less hungry.

We heated up frozen chicken and rice soup for dinner and managed to get in bed a bit earlier than the night before.

Day 3, another sunny day after a calm but cold night. Eric’s watch measured a temperature of about -20 inside the tent in the morning, so we guessed it was about -20 or -25 overnight.

We carried a cache of food and fuel to Camp 2 around 4100m and then returned to Camp 1 with our sleds strapped to our backs. This was much easier than skiing with the sled dragging behind us, but turned us into human sails, so we skied cautiously. We ate more consistently throughout the day and felt far better than the day before.

Around midday we began to hear helicopters and planes and assumed groups were being dropped off on King’s Trench and possibly the East Ridge.

Day four, May 17, was our first rest day. We read, organized gear and food, and focused on acclimating. We saw our first signs of human life on this day when we saw another group drop a cache a few km down the trench from us.

Camp 2: Days 5-10 (May 18 – 23)

We were now on day 5, May 18. We packed up and got moving, excited to head up to camp 2 (4100m). It took us about 5 hours to ski 6km with 850m of elevation gain. It was hot all day but once we arrived at camp 2, the wind was hammering and we cooled down quickly. We made quick work of setting up camp and had dinner at a reasonable hour.

We both got a mild headache in the evening and went to bed early. We woke up the next morning, day 6, to a full whiteout, but our headaches were gone. We took another rest day because of the weather, and through breaks in the whiteout, watched the snow load, and then reverse load, the 40 degree slope that would take us to camp 3.

Camp 2 is perched on top of a sloping hill, exposed to wind from the east and west, and is positioned below the McCarthy Gap. The McCarthy Gap, one of the only technical sections of the King’s Trench route, is a 450m high 40 degree slope with icefall on both sides and at the top.

At one point in the day we geared up and went on a small tour to check out the McCarthy Gap. We made it a few hundred metres, to the base of the slope, before we called it due to high winds and poor vis.

We hired Chris Tomer to provide us with forecasting services via our InReach, and we were also getting weather forecast information from our friend Eric. Eric had planned to attempt the East Ridge around the same time as us but hadn’t even made it in to basecamp due to a 10ish day weather delay. They made the smart decision to pull the plug and try again next year after having lost most of their vacation days to weather. Both Chris and Eric let us know there was precipitation forecasted on and off for the next week or more.

The next few days were about the same. Some sun but mostly poor vis and snow, which would have been fine if we didn’t need to ascend a loaded 40 degree slope. We made the decision not to put a skin track up the obviously loaded slope for a number of reasons. First, like I mentioned, the slope was 40 degrees and loaded with recent storm snow. Second, there were only two of us, so if anything went wrong, only one person could perform a rescue. Third, the flight to Mt Logan is minimum one hour, and flights can only happen in good weather (Sian told us in general, weather is good enough to fly to Logan about 50% of the time). We are both conservative decision makers in avalanche terrain, and we brought this style of decision making to Mt Logan.

A few days into our time at Camp 2, other parties began to trickle in. First, our four friends from Montana arrived. They were a group of four with 3 mountain guides and one engineer. Most of them had guided Denali several times. Like us, they felt the McCarthy gap looked too loaded to climb and planned to wait a few days for the snowpack to settle.

In between breaks from digging holes and building double-thick snow walls three-hundred-and-sixty degrees around our tents, we passed the time by skiing powder/windpress laps below camp, reading, and eating more butter ramen.

By May 22, Camp 2 was feeling nicely full. We had our Montana friends next door, a group of two men from Colorado who had also climbed Denali a few times, and a huge guided group of 8 out of Nelson. The lead guide had climbed Logan 11 times, and in his own words, he liked to wait two years between his trips in order to “forget how shitty it is here”. Our time alone on the glacier now felt very far away, and it was nice to see and hear other people in the desolate wasteland.

The 11-time Logan guide decided to put a skin track up the McCarthy Gap with two of the other guides in his group as safety spotters (ie waiting in a safe spot at the base of the slope in case a rescue was needed). When we had asked him earlier if he had ever seen the slope avalanche, his response was “Oh yeah, it’s avalanched on me before!” We sat in camp (just kidding, we were probably either digging holes or building walls) and watched him ascend the slope without incident and then ski down. After that, everyone in camp suited up to ski that slope, knowing more weather was incoming and it could be helpful to get some tracks into it before the next snowfall. It was a fun ski and we were grateful to be doing something other than digging holes.

We were starting to worry about our timeline. We had lost a few days at the beginning waiting to fly in, and we had now lost quite a few more days to weather. We both had to be back at work on June 3 and hadn’t had the foresight to request vacation days for the first week of June after losing those days at the beginning. Chris and our friend Eric were both telling us there was no weather window in the forecast.

We knew we needed a minimum of 7 days to get from Camp 1 to the summit, plus a day to get back down to basecamp and at least a few contingency days for weather. Even if we got an 8 day weather window, which we definitely didn’t have, we would likely not make it back to the airstrip in time to go to work on Monday, June 3. We started to talk about heading back to basecamp to catch the next available flight out rather than travelling higher on the mountain, knowing we didn’t have time to summit anyways.

On May 23, we made the call to head back down, and so did the group of 2 from Colorado. We asked them why and they said they weren’t enjoying themselves, that Logan was much more difficult and hostile than Denali. The Montanans also told us that Denali is far more approachable. It’s less remote, warmer, and has a ton of people and infrastructure compared to Logan. The weather is also less hostile.

We packed up camp and skied down, cursing our full sleds as they flipped over, dragged us to the side, and generally tried to kill us.

Basecamp: 3 days of hope and despair

We arrived in basecamp with mixed emotions. On the bright side, we were gonna get out of this hellscape! On the other hand, we had started to kind of like this place. Our systems were getting super dialed, and we had become excellent hole diggers and wall builders.

We contacted Sian and she let us know she’d try to get us out as soon as she could, likely May 24 or 25. So we waited.

On May 25, Sian sent a plane to us, we packed up camp and were ready to go, but it had to turn around because we were totally socked in. It felt tragic and I spent a while lying on top of our luggage and crying, sure I’d never escape basecamp. Later that day we went for a flat and boring ski down the glacier towards the US border.

On May 26 we successfully flew back to Silver City. We were super excited to get on the plane, but as soon as it took off, we both felt like we weren’t ready to leave yet. I think we made the right calls, besides not asking for more days off before we left. While it felt unfortunate to leave without summitting, in reality that’s just how it goes sometimes.

Our friends from Colorado had to wait a few more days to fly out as a storm came in just after we flew out, bringing about 1 metre of snow. Our friends from Montana and the guided group all made it to the summit at the end of May/beginning of June, working with a very short weather window, having spent several more days waiting out the weather.

Some Key Gear

Reach out if you’d like the full spreadsheet 🙂

Tents

- Mountain Hardware Trango 3 for sleeping. A great tent, spacious for two people.

- BD Megalight as our kitchen tent. Unfortunately one of the sides got a little rip in the wind at camp 2.

Sleeping bags & mats

- Coral: Big Agnes Cinnabar -30, Big Agnes insulated plus Z lite

- Eric: Thermarest Polar Ranger -30, Big Agnes non-insulates plus Z lite

- Lightweight foam sheet for tent floor

Stoves

- Borrowed MSR Whisperlite (thanks Em!)

- MSR XKG, sounds like a jet engine but melts snow like a charm

- MSR Reactor as backup with a few fuel canisters

Clothing

- Coral

- Feathered Friends Khumbu expedition parka as warmest outer layer

- Arc’teryx Alpha Lightweight Parka as outer layer (this jacket is super warm, light, and versatile, with a relatively waterproof exterior)

- Arc’teryx Proton as mid layer jacket

- Arc’teryx Alpha Hybrid softshell pants

- Arc’teryx Rho heavyweight bottoms & Rho merino bottoms, Arc’teryx Taema sun hoody, Arc’teryx Delta 1/2 zip hoody

- An assortment of mitts including BD Mercury Mitts, which I wore most, and Showa gloves for camp setup. Also a pair of OR expedition mitts.

- My cursed BD Couloir harness which is terribly designed, the buckle sits on my hip bone and bruises me.

- Eric:

- Feathered Friends Khumbu expedition parka as warmest outer layer

- Arc’teryx Atom AR as main outerlayer

- Arc’teryx Proton as midlayer

- Arc’teryx Gamma Guide pants

- Ancient Patagonia R1, Arc’teryx wool bottoms, Kuhl sun shirt

- Showa gloves for camp setup, OR Stormtracker, BD Guide gloves, and more.

Skis & ski gear

- Coral: Line Pandora 104s with ATK Raider 11 EVO bindings, Pomoca mohair mix skins, Scarpa Gia boots, and trusty old G3 poles.

- Eric: Black Crows Navis Freebird with G3 Z bindings, G3 skins, Scarpa F1LT boots, and G3 poles as well.

Sleds: we bought expedition sleds from home hardware and laced them up with cord at home, using PVC pipes to make the attachment to our harnesses stiff. It sort of worked.

Some takeaways for the next trip

- Eat more often than we want to, it’s easy to not eat enough and bonk quickly. For me (Coral), bonking meant I got really cold.

- Have a bigger time window. We should have booked 4 or 5 weeks off work and adjusted our days off once it looked like we’d fly in the next day. Being tight for time on the glacier was what ultimately made us turn around and we likely could have stayed an extra week if we had the foresight to reschedule a few meetings and book the days off. As it was, doing all of that through an InReach felt unprofessional.

- Change into warm clothes as soon as camp is set up. Sweaty clothes get cold quickly, and once we got cold, it was really hard to warm up again.

- The forecast needed to be multiplied by 10. For example, if the forecast was calling for 1cm of snow, we’d likely get 10. If it was calling for light wind, we’d be getting out of our tent every few hours to reinforce our snow walls. Clear, calm days were a gift and we got 3 of them.

- Butter ramen is the best meal and can be eaten for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. Butter ramen is exactly what it sounds like: ramen with butter. We also added dehydrated kale to our ramen, which made it even more delicious.

- Hot chocolate LMNT was a great way to get electrolytes without drinking cold water.

- Having a camp setup system is key. Doing it the same way each time is efficient, effective, and foolproof.

- Digging holes is the main thing we did on this expedition. Have a good shovel and make time for mobility, stretching, and core work so that you can continue to dig holes.